She helped found a Mining Empire

Hope Hancock, wife of millionaire prospector Lang Hancock, has two outstanding characteristics: She genuinely cares for people, and she complements her husband in the home, in his work, and in his tough, adventurous way of life.

TWENTY-ONE years ago Mrs. Hancock began married life in a caravan near an isolated goldmine. Today, in her spacious home in Perth, she retains her keen interest in her husband’s essentially man’s world of mining, and still accompanies him on many exploratory trips.

Now she is wholeheartedly behind his current project: to save the small mining town of Wittenoom, in the north-west of Western Australia, from extinction. When the Colonial Sugar Refining Company announced at the end of last year it was going to close down its blue asbestos mine at Wittenoom, it looked as though the town’s population of 1100 miners and their families would have to find new jobs and new homes.

Then came the news that Lang Hancock and his business partner, Peter Wright, both in their late fifties, had bought Wittenoom, were going to reopen the mines and search for new asbestos deposits. The town, according to Hancock and Wright, was not only going to live, it was going to grow and prosper.

Hundreds of people with a stake in the north-west and many, many more who were just interested wrote to the two men to say thank you. Personal thanks Some of the letters so touched Mrs. Hancock that she went round visiting the writers who lived in Perth to say a personal thank-you for their interest.

This act symbolises the essence of Hope Hancock. Yet all she will say is, “I am an ordinary woman married to a remarkable man.” She underestimates herself, for she is as near the complete person as anyone I have met. Mrs. Hancock describes the gold mine where they had their first home – a caravan – as “a hole in the ground.”

It was 100 miles from Wiluna, in the north-west, and her only neighbours were three men who lived in a nearby hut. “But I loved the life,” she said, looking back on those early days. “I had been brought up on a north I west station where conversation revolved round windmills, sheep, and fences, and to go into the new world of mining was very stimulating.”

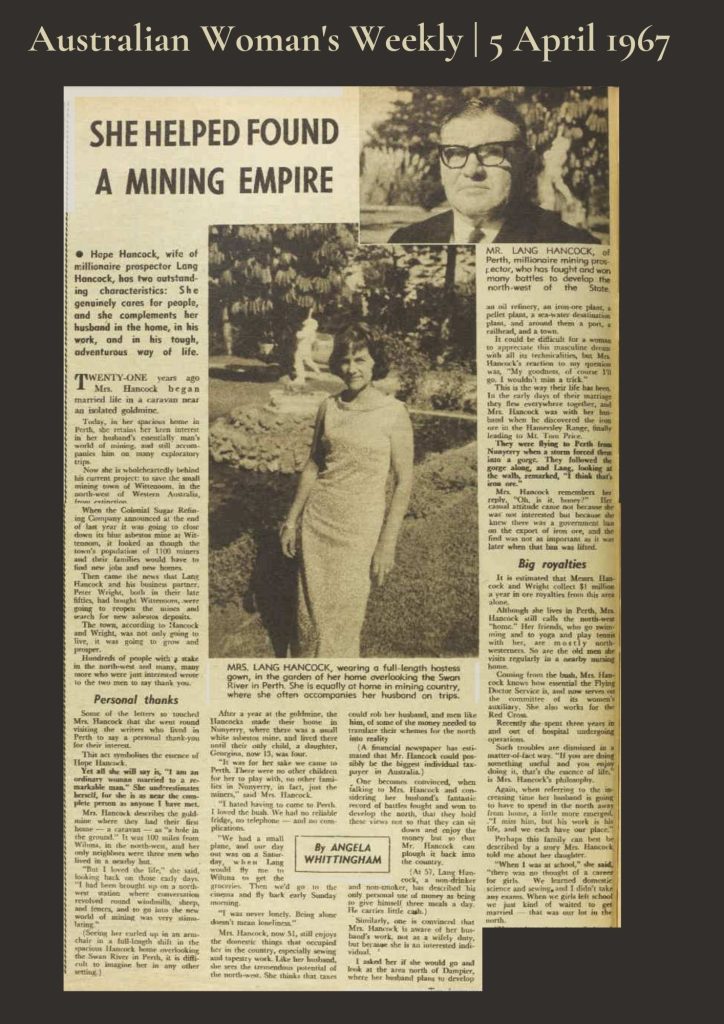

Seeing her curled up in an arm I chair in a full-length shift in the spacious Hancock home overlooking the Swan River in Perth, it is difficult to imagine her in any other I setting.

She is equally at home in mining country, where she often accompanies her husband on trips. After a year at the goldmine, the Hancocks made their home in Nunyerry, where there was a small white asbestos mine, and lived there until their only child, a daughter, Georgina, now 13, was four. “It was for her sake we came to Perth. There were no other children for her to play with, no other families in Nunyerry, in fact, just the miners,” said Mrs. Hancock.

“I hated having to come to Perth. I loved the bush. We had no reliable fridge, no telephone – and no complications. “We had a small plane, and our day out was on a Saturday, when Lang would fly me to Wiluna to get the groceries. Then we’d go to the cinema and fly back early Sunday morning.

“I was never lonely. Being alone doesn’t mean loneliness.” Mrs. Hancock, now 51, still enjoys the domestic things that occupied her in the country, especially sewing and tapestry work. Like her husband, she sees the tremendous potential of the north-west. She thinks that taxes could rob her husband, and men like him, of some of the money needed to translate their schemes for the north into reality.

A financial newspaper has estimated that Mr. Hancock could possibly be the biggest individual tax- payer in Australia. One becomes convinced, when talking to Mrs. Hancock and considering her husband’s fantastic record of battles fought and won to develop the north, that they hold these views not so that they can sit down and enjoy the money but so that Mr. Hancock can plough it back into the country.

At 57, Lang Hancock, a nondrinker and nonsmoker, has described his only personal use of money as being to give himself three meals a day. He carries little cash. Similarly, one is convinced that Mrs. Hancock is aware of her husband’s work, not as a wifely duty, but because she is an interested individual.

I asked her if she would go and look at the area north of Dampier, where her husband plans to develop an oil refinery, an iron-ore plant, a pellet plant, a sea-water desalination plant, and around them a port, a railhead, and a town.

It could be difficult for a woman to appreciate this masculine dream with all its technicalities, but Mrs. Hancock’s reaction to my question was, “My goodness, of course I’ll go. I wouldn’t miss a trick.” This is the way their life has been. In the early days of their marriage they flew everywhere together, and Mrs. Hancock was with her husband when he discovered the ii on ore in the Hamersley Range, finally leading to Mt. Tom Price.

They were flying to Perth from Nunyerry when a storm forced them into a gorge. They followed the gorge along, and Lang, looking at the walls, remarked, “I think that’s iron ore.” Mrs. Hancock remembers her reply, “Oh, is it, honey?” Her casual attitude came not because she was not interested but because she knew there was a government ban on the export of iron ore, and the find was not as important as it was later when that ban was lifted.

Big royalties It is estimated that Messrs. Hancock and Wright collect $1 million a year in ore royalties from this area alone. Although she lives in Perth, Mrs. Hancock still calls the north-west “home.” Her friends, who go swimming and to yoga and play tennis with her, are mostly north westerners.

So are the old men she visits regularly in a nearby nursing home. Coming from the bush, Mrs. Hancock knows how essential the Flying Doctor Service is, and now serves on the committee of its women’s auxiliary.

She also works for the Red Cross. Recently she spent three years in and out of hospital undergoing operations. Such troubles are dismissed in a matter-of-fact way. “If you are doing something useful and you enjoy doing it, that’s the essence of life,” is Mrs. Hancock’s philosophy.

Again, when referring to the increasing time her husband is going to have to spend in the north away from home, a little more emerged. .”I miss him, but his work is his life, and we each have our place.”