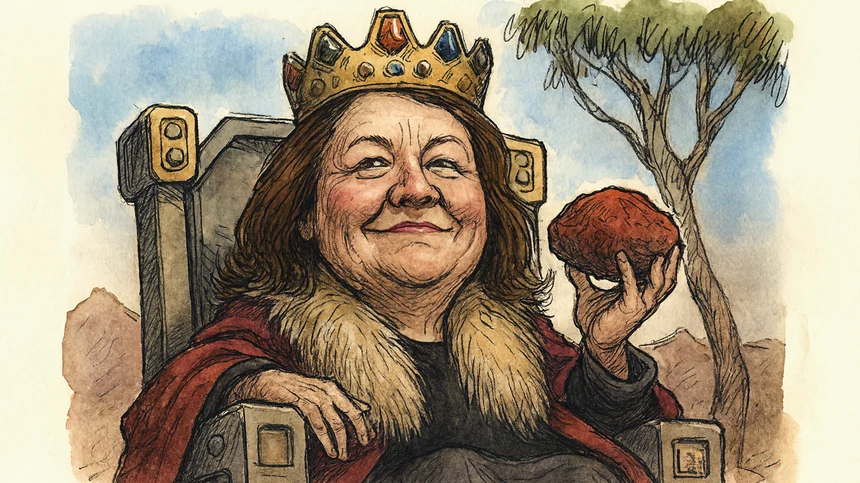

Gina’s global grab: Iron ore queen to critical minerals empress?

Article by Scott North, courtesy of Mining.com.au

02.08.2025

“Who the bloody hell is Gina Rinehart?”

If you lob that question into an office in London or on a Houston drill rig, heads will swivel. Back in Perth, everyone knows she’s Australia’s richest person and executive Chair of Hancock Prospecting, with a fortune of roughly $38 billion.

Her flagship Roy Hill mine pushes out more than 60 million tonnes of iron ore a year, helping turn her into a global iron ore powerhouse. By paying down the US$7.2 billion ($11.1 billion) project debt within five years, Rinehart created a massive financial surplus and she’s spending it on lithium, rare earths, copper, potash and gas.

Rinehart’s pivot feels less like a billionaire hobby and more like a calculated realignment of global critical mineral power. So how did a private iron ore outfit end up holding influential stakes in rare earth champions, battery metal prospects and potash royalty streams? And what does it mean for resource security in Canberra, Washington and Berlin?

Few know that by the end of 2016, Rinehart’s pastoral portfolio spanned more than 1.5% of Australia’s land mass with a total of 21 stations, crowned by her S. Kidman & Co acquisition and bolstered by the Roy Hill cattle station buy-out in the Pilbara.

She’s also quietly generous – through Hancock Prospecting and her Georgina Hope Foundation she’s backed swim stars and breast cancer research, visited orphanages in Cambodia and gifted Swimming Australia AU $10 million in 2012. In late 2023 she even snapped up Chrome Park station near Hamilton, Victoria for $8.6 million – proof she’s as comfortable in gumboots as she is in the boardroom.

Every empire needs a cash engine

Rinehart’s is Roy Hill, an iron ore behemoth she took from contested tenement to 70‑million-tonne-per-year export machine. In 2012 she secured US$7.2 billion in project finance to build it.

Sceptics questioned whether a private company could handle that debt, by 2019 the mine was turning out 60 million tonnes a year and by 2021 had approval to push to 70 million tonnes. It shipped about 64 million tonnes last fiscal year and delivered net profit after tax of $3.2 billion. Crucially, all US$7.2 billion of borrowing was repaid within five years.

Roy Hill is more than a pile of ore, it’s proof Rinehart and her team can execute. A workforce north of 4,000, a fully integrated rail‑port chain and pink mining trucks raising breast cancer awareness show Hancock can deliver complex projects at industrial scale. For investors and governments, those operational metrics matter and they underwrite Rinehart’s next chapter.

The first pivot out of iron ore? Lithium. In 2023, Rinehart quietly built an 18% blocking stake in Azure Minerals and then teamed up with Chilean giant SQM to offer $1.7 billion for the company. That joint bid, completed in 2024, gave Hancock and SQM equal ownership of Azure’s Andover project. The model was clear, take meaningful equity positions rather than risk billions on greenfield projects alone.

Rare earths came next. Hancock took 10% of Arafura Rare Earths (ASX:ARU), owner of the Nolans project in the Northern Territory. In April 2024, Rinehart took 5.3% of MP Materials (NYSE:MP) in the US and days later bought 5.82% of Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths (ASX:LYC). She even took 5.85% of Brazilian Rare Earths (ASX:BRE) ahead of its ASX debut.

A theme started to emerge

Rinehart spread bets across the value chain from exploration to processing to ensure she always has a seat at the table.

In March 2024, Hancock’s Ecuadorian subsidiary, Hanrine, paid $186.4 million to take 49% of six mining concessions in Ecuador’s Andean copper‑gold belt. Weeks later Rinehart agreed to fund up to $120 million of exploration to earn as much as 80% of Titan Minerals’ (ASX:TTM) Linderos project. Now she is moving into the same neighbourhood as Barrick Mining (TSX:ABX), Zijin Mining (SSE:601899) and Anglo American (LSE:AAL).

And then there was Potash. In 2016, Hancock spent about $380.6 million on a revenue royalty for the Woodsmith Potash Project in the UK. The deal gives her 5% of revenue on the first 13 million tonnes of fertiliser and 1% thereafter, plus a 20,000 tonne annual offtake option.

Woodsmith now sits in Anglo American’s hands, which has slowed development following a failed merger with BHP (ASX:BHP). Should Woodsmith eventually come online, Hancock collects royalties without the capital pain of building a mine.

How do markets feel about Rinehart’s shopping spree? Opinions diverge. Dylan Kelly of Terra Capital told the Australian Financial Review that Hancock’s stake in MP Materials could bring “Roy Hill–type cash flow” because non‑Chinese rare earth producers enjoy strategic pricing power.

Some investors speculate that holding positions in both Lynas and MP Materials could restart their stalled merger talks. Others point out the obvious – a 10% piece of Arafura, 5.3% of MP Materials and 5.82% of Lynas mean Rinehart will have a voice if consolidation happens.

Being private is a double edged sword. On one hand, Rinehart doesn’t have to share her playbook. She can negotiate quietly, build positions quickly and pivot without alerting rivals. That freedom helped her stop Albemarle’s (NYSE:ALB) Liontown Resources (ASX:LTR) takeover by building a stake and later pivoting to support SQM’s (NYSE:SQM) offer.

On the flip side, analysts estimate Hancock made $5.6 billion in profit in FY2024, but there’s no official confirmation. For regulators focused on supply chain transparency, that secrecy complicates things.

So what’s the endgame?

Three themes stand out. First, Rinehart’s critical minerals bets dovetail with Western governments’ desire to reduce reliance on China. By holding material stakes in Arafura, MP Materials and Lynas, she positions herself as a cornerstone investor in a non‑Chinese rare earth supply chain.

Second, the “equity grenade” approach, small but strategic stakes gives Hancock upside without heavy construction risk. Deals with Azure, Titan and Germany’s Vulcan Energy (which produces battery grade lithium brine) exemplify this. Third, geographic spread equals policy insurance. By investing across Australia, the US, Ecuador, Brazil and the UK, Hancock is hedging against any single country’s regulatory mood swings.

These moves also intersect with Rinehart’s agricultural interests. The Woodsmith royalty ties fertiliser supply to her cattle operations, and her public speeches champion nuclear energy over wind farms to protect farmland. Owning slices of potash, lithium and rare earths gives her a louder voice in debates on land use, export controls and strategic reserves.

Rinehart’s portfolio mirrors wider trends in resource nationalism. Governments in Africa and Latin America are insisting on local processing and bigger revenue shares. Instead of hoarding speculative leases, she’s buying into projects with clear timelines.

In Ecuador she partnered with state‑owned ENAMI in a region where social licence is fragile but grades are “world class”. In Brazil, Rinehart’s stake in Brazilian Rare Earths provides exposure to high‑grade monazite sands. In Germany, her 7.5% stake in Vulcan Energy (ASX:VUL) aligns with the EU’s drive for domestic lithium.

Taken together, these investments suggest Rinehart wants to shape the critical minerals landscape rather than merely profit from it. As Australia’s largest private miner and a vocal free market advocate, she can influence trade negotiations and national security debates. Partnering with state entities in Ecuador and giants like SQM in Australia builds coalitions capable of countering China’s dominance.

Ultimately, Rinehart’s diversification isn’t about walking away from iron ore. It’s about using iron ore cash flows to bankroll the minerals that will drive the green transition and food security. The old playbook, sell iron ore to China and hope for the best, isn’t her playbook.

Whether you call her iron ore queen or critical minerals empress, the fact is she’s positioning herself as the West’s go-to partner for iron, lithium, rare earths, copper, potash and more. Governments, investors and rivals should take note the next decade of mining could well be her crowning achievement.